Upon encountering its intricately spun web, one might pause to observe Gasteracantha cancriformis, commonly known as the Spiny Orb Weaver. This fascinating arachnid stands out among Florida’s spider fauna due to its distinctive morphology and web characteristics. Widely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions globally, from the southern United States to northern Argentina, this species commands attention. This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the Spiny Orb Weaver, covering its identification, ecological role, and unique biological attributes, to enhance appreciation for this remarkable garden inhabitant.

Meet the Spiny Orb Weaver: A Master of Disguise (and Spin!)

Identifying Your Eight-Legged Neighbor

The Spiny Orb Weaver exhibits notable sexual dimorphism, with females being significantly larger and more conspicuous than males.

Female Appearance

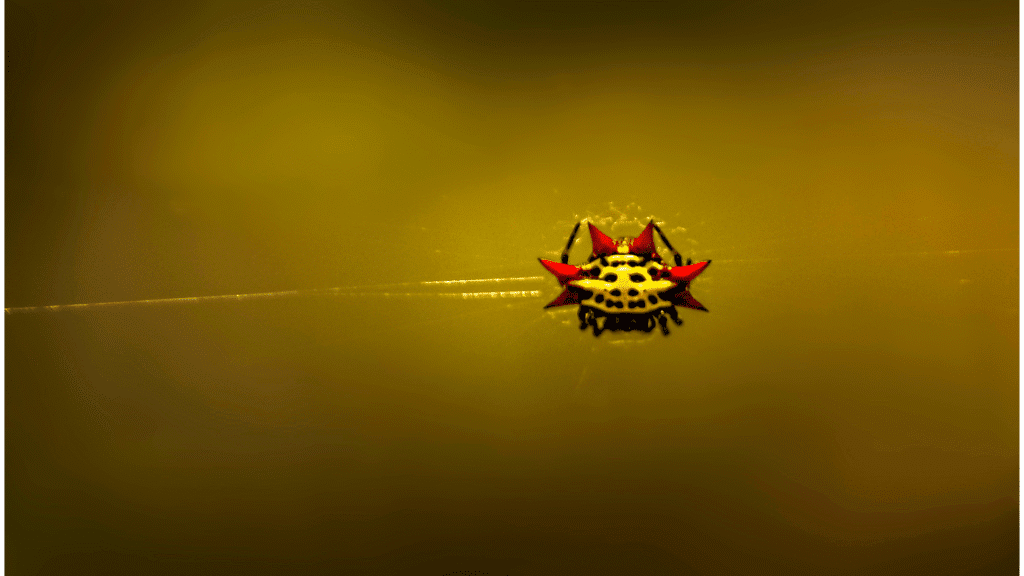

Female Gasteracantha cancriformis typically measure 5 to 9 mm in length and 10 to 13 mm in width. Their most striking feature is their six prominent, pointed abdominal projections, frequently referred to as “spines”. While specimens in Florida commonly present with a white abdominal dorsum, black spots, and red spines, color variations exist, including yellow or orange abdomens, black spines, or even an almost entirely black dorsal and ventral coloration. The carapace, legs, and venter are typically black.

Male Appearance

Males are considerably smaller, ranging from 2 to 3 mm in length. Unlike females, they lack the prominent abdominal spines, possessing instead four or five small posterior humps. Their coloration is similar to that of the female, though the abdomen is gray with white spots.

What’s in a Name? Debunking the “Crab Spider” Myth

Gasteracantha cancriformis is “crab spider” due to its distinctive crab-like shape and hardened, spiny abdomen. However, it is crucial to clarify that these spiders are not taxonomically related to the true crab spiders (family Thomisidae). Other common designations include Spinybacked Orbweaver, Spiny Spider, Jewel Spider, or Thorn Spider.

Are Spiny Orb Weavers Dangerous?

Spiny Orb Weavers are non-aggressive spiders. When threatened, their primary response is typically to flee. A bite is generally mild, causing localized pain, numbness, and swelling comparable to a bee or wasp sting. Long-term symptoms are uncommon unless a severe allergic reaction occurs. Their spines can also cause a minor skin puncture if inadvertently touched.

Garden Guardians: Their Beneficial Role

Gasteracantha cancriformis are valuable beneficial insect predators. They play a significant role in controlling populations of various small insects. They are particularly valuable in Florida’s citrus groves, where they assist in pest control for agricultural purposes.

Management Tips

A tidy garden, by pruning shrubs and removing dead leaves and waste, can reduce potential hiding places, making the area less appealing to them. If a removal is deemed necessary, the spider and its web can be carefully relocated to a more suitable outdoor area. An abundance of spiny orb weavers may indicate a broader insect pest issue, potentially warranting investigation and targeted pest management by a professional.

Beyond the Spines: Unveiling Their Secret Lives (Unique Insights!)

The Spider with a Jet Lag: A 19-Hour Internal Clock

Spiny Orb Weavers are reported to possess an unusual 19-hour circadian rhythm, or internal clock. This deviation from the typical 24-hour day-night cycle on Earth presents a scientific anomaly. Research generally suggests that animals with such mismatched internal clocks often experience health issues in their offspring; however, G. cancriformis appears to defy this trend, successfully perpetuating its life cycle. This unique characteristic offers a fascinating, unexplained biological mystery.

More Than Just Sticky: The Surprisingly Toxic Web

While not explicitly detailed for G. cancriformis, research on other orb-weavers, such as the banana spider (Trichonephila clavipes), reveals a sophisticated chemical strategy within their webs. The sticky droplets on orb-weaver webs are known to contain a complex mixture of substances, including over 200 toxin-like proteins, peptides, and fatty acids. These compounds can act as neurotoxins, capable of paralyzing prey on contact without requiring an immediate bite from the spider. For instance, palmitic acid, abundant in web glue, can corrode an insect’s waxy coating, facilitating toxin penetration. Some components in the web glue may even initiate pre-digestion of insects while they are still entangled. This chemical approach is hypothesized to be a more energy-efficient method for the spider to secure smaller prey than immediate venom injection and silk wrapping. It raises an intriguing question about whether G. cancriformis employs a similar “toxic lair” and the evolutionary benefits it might provide.

Social Spinners? Glimpses of Communal Webs

The sources indicate that some Spiny Orb Weavers may exhibit semi-social behavior, forming shared webs with conspecifics by integrating parts of their neighbors’ webs. This communal arrangement offers potential advantages, such as reduced individual effort in web construction. However, it also introduces potential drawbacks, including increased vulnerability of grouped egg sacs to parasites.

Spines for Survival: A Closer Look at Defense

The distinctive abdominal spines of Gasteracantha cancriformis are hypothesized to serve an anti-predator function. Additionally, their relatively small size, averaging less than half an inch in length, can make them difficult for predators to detect and attack. Known predators of Spiny Orb Weaver eggs include parasitoid wasps and flies, such as Phalacrotophora epeirae and Arachnophaga ferruginea. Adult spiders may fall prey to wasps and other spiders, with jumping spiders specifically noted for their tactic of luring orb weavers from their webs.

A Year in the Life: Biology and Web Mastery

Habitat and Distribution

Gasteracantha cancriformis belongs to a pantropical genus, and it is the only species of its genus found in the New World. Its range extends from the southern United States (from California to Florida) down to northern Argentina, Central America, Jamaica, and Cuba, and it has also been introduced to Hawaii. These spiders thrive in warm, humid environments, commonly inhabiting woodland edges, shrubby gardens, trees, shrubs, and especially citrus groves. They establish their webs in areas that provide suitable structures for support.

The Art of the Orb Web

Female Spiny Orb Weavers exhibit remarkable web-building skills, typically constructing a new, intricate orb-shaped web each night to ensure its security and stickiness. The catching area of the web can measure 30 to 60 cm in diameter. Conspicuous tufts of silk, known as stabilimenta, are often found on the foundation lines of the web. While their precise function remains unknown, one hypothesis suggests they make the webs more visible to birds, thereby preventing accidental destruction. Webs can be situated at heights ranging from less than 1 meter to over 6 meters above ground, including in trees, bushes, and building corners.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

As previously noted, Spiny Orb Weavers exhibit pronounced sexual dimorphism in size. Their lifespan is relatively short; males typically die shortly after mating (within a few days), and females perish after laying their eggs, usually with the arrival of the first frost in colder regions, generally living less than a year.

Breeding predominantly occurs during the winter months. Females are most prevalent as adults from October through January, while males are most common in October and November. Mating behavior observed in laboratory settings indicates that males approach female webs, using a four-tap rhythmical drumming pattern on the silk to gain attention. Mating can last 35 minutes or more and may occur repeatedly. Post-mating, the male remains on the female’s web.

Ovate egg sacs, measuring 20 to 25 mm long by 10 to 15 mm wide, are deposited on the undersides of leaves adjacent to the female’s web from October through January. Each egg mass typically contains 101 to 256 eggs, with an average of 169. The female constructs a complex egg case: eggs are laid on a white silken sheet, covered with a tangled mass of fine white/yellowish silk, then secured with strands of dark green silk, and finally enveloped by a net-like canopy of coarse green and yellow threads. This elaborate construction provides protection for the eggs and developing spiderlings. Eggs hatch in 11 to 13 days. Spiderlings remain within the egg sacs for an additional two to five weeks in the field before dispersing.

Conclusion: Appreciating Nature’s Oddities

The Spiny Orb Weaver, Gasteracantha cancriformis, is a truly unique arachnid, combining striking beauty with a non-threatening nature and significant ecological benefit. From its distinctive spiny appearance and intricate web designs to its surprising 19-hour internal clock and potentially toxic silk, these spiders are wonders of the natural world. Recognizing their role in controlling insect populations and observing their complex behaviors allows for a greater appreciation of these small yet vital contributors to our ecosystems.

No, Spiny Orb Weavers are generally considered harmless to humans. Their bites are mild, causing symptoms comparable to a bee sting, and serious effects are uncommon. They are not aggressive and are more likely to flee than bite.

Male Spiny Orb Weavers are considerably smaller than females, typically measuring 2 to 3 mm in length, and they lack the prominent abdominal spines seen in females. Their abdomen is generally gray with white spots. Males are infrequently observed by humans.

Spiny Orb Weavers are insectivorous predators. They primarily feed on small flying and crawling insects caught in their orb webs, including flies, mosquitoes, moths, beetles, and whiteflies.

Spiny Orb Weavers have a short lifespan, typically living less than a year. Males die shortly after mating, and females perish after laying their egg sacs, usually with the onset of cold weather.

Yes, female Spiny Orb Weavers commonly construct a new, intricate orb-shaped web each night. This daily reconstruction ensures the web’s security and stickiness for optimal prey capture.